France Joins the Space Age Club

|

|

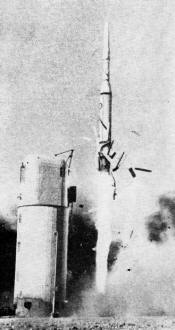

France Joins the Space Age ClubTransmission from France's first satellite was late, weak and short-lived, but it proved that the Diamant booster worked - and well. The successful launch of its first satellite was technically unimpressive but it became a membership card in the world's most exclusive organization By Robert Farrell Paris News Bureau The 88-pound satellite that roared into orbit from its launch pad in the Algerian Sahara November 26 was not a complete technical success, but it was a resounding political coup. It made France a member of one of the most exclusive and costly clubs in the world - the space age club. There are only two other members - the United States and the Soviet Union. The A-1 satellite's main purpose - to test the French-developed, three-stage Diamant booster - was accomplished: the booster worked well. Transmission from the satellite, however, was almost a flop: one of the satellite's four antennas apparently was damaged during powered flight. This lack of transmission almost spoiled the second purpose of the launch - to test France's two satellite ground station networks, called Diane and Iris. Diane consists of tracking stations at the Hammaguir launch base in the Sahara and Pretoria, South Africa. Iris has telemetry and control stations at Hammaguir, Pretoria, Ouagadougou in West Africa, and in Beirut, Lebanon. During the first orbit, neither Iris nor Diane picked up a signal. On the second pass, Hammaguir picked up a faint noise - enough to know the A-1 was in orbit. The equipment on board the satellite - for the most part silent - consists of a radar transponder and two transmitters; one is a beacon and the other is for telemetry. Batteries on board were supposed to keep the equipment going for 15 days. The orbit was intended to last a year, and probably will since the 330-mile perigee and the 1,090-mile apogee keep it above atmospheric drag. The period of revolution is 108 minutes. I. Space Budget France's space program, of course, is modest by comparison with programs in the United States and Soviet Union. France currently is spending only 1 percent of the amount the U.S. is spending, and no man-in-space project is planned. In 1962 when France's civil space program got under way, the Centre National d'Etudes Spatiales (CNES) - the French equivalent of the U. S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration - had a budget of approximately $18 million. This year, the CNES budget is up to $57 million and in 1966 will total $74 million. Actually, CNES officials complain that they are getting about 40 percent less than they are requesting. General Robert Aubiniere, CNES boss, considers an annual $100-million budget to be a minimal one. The space agency, in fact, has been forced to limit its programs because of the budget squeeze. Still, it's misleading to judge French space efforts entirely by the CNES budget. Because France has military ambitions, including the development of long-range, ground-to-ground strategic missiles and Polaris-type missiles for nuclear submarines, there is a good deal of military fallout on the French civil space effort. CNES Diamant launcher is an example. The rocket is being financed almost entirely by the French defense ministry. So, the development of this $100-million CNES booster has not cost the space agency any budgetary headaches. Yet it's the Diamant that has enabled France to proclaim itself number three in space. II. Space Plans France's A-1 satellite, launched November 26, should stay up about a year. The satellite succeeded in one mission and flopped in another. The booster worked well, but the transmission in flight was poor, apparently because of a damaged antenna. France, however, does not intend to confine its space effort to national programs. It is participating in the European space launcher project by building the second stage of the Europa rocket. It is also working on a satellite program with NASA. The first one, designated FR-l, was scheduled to be launched Dec. 6 by a NASA Scout booster from Vandenberg Air Force Base, Calif. The FR-1 satellite, designed and developed by CNES, is France's first scientific satellite. Scheduled to be launched into a near-polar orbit, the FR-1 was designed to measure the effects of the earth's magnetic field on very-low-frequency propagation. The experiment was to involve continuous radiation of signals from two ground stations, one in France and the other at Balboa, Panama. The satellite antenna system was to assist in tracking vlf signal propagation along the flight path and in measuring signal strength direction and signal-noise ratio. Three more satellites will be launched from Hammaguir powered by Diamant boosters in January, the 80-pound D-1 satellite will go up - the first French scientific satellite orbited by a French booster; later, the D-1B; and in mid-1967 the 175-pound D-1D. After mid-1967, the French will shift their space shots to a new $60-million launch center now under development in French Guiana, in South America. This base, which will employ some 25,000 people, will not be completely finished until 1969 [Electronics November 1, p. 159]. In all, the French have orbited one satellite and scheduled four more flights. In addition, the French hope to work out a new agreement with NSA for launching a meteorological satellite with a NASA booster sometime in 1967 to 1968. III. Market As might be expected, the bulk of the electronics business is handled by French electronics companies such as Compagnie Francaise Thomson-Houston and the Compagnie Generale de Telegraphie Sans Fil (CSF). One of the reasons for the French effort is to keep its companies proficient in advanced technology. Initially, the French leaned on a U.S. supplier for such satellite components as silicon cells but now these items are being developed by Societe Anonyme de Telecommunications. U.S. companies are involved if they have French affiliates, such as the International Telephone and Telegraph Corp.'s wholly-owned subsidiary, Laboratoire Central des Telecommunications (LCT). They can also sell to France if they develop equipment so superior that the French have no recourse but to buy from the U. S. When France moves its space activities to French Guiana, there may be more opportunity for U. S. business. Although CNES has already ordered its two big tracking radars from Thomson-Houston - similar to the Radio Corp. of America's AN/FPQ-16 missile range standbys - two digital computers must still be purchased and two new telemetry stations must be outfitted. France hopes the favorable location of the site for launching will attract many foreign users.

Posted December 6, 2023 |

|